Why Your $3 Drug Costs $10 with Insurance

PBMs profit on confusion. Here’s how startups are breaking the silence.

Bullets to sound smart with your friends (or your boss):

Opacity drives PBM profit — even insurers don’t see the full flow, and three firms control 80% if the market

Spread pricing skims the middle — PBMs pocket the difference between what plans pay and what pharmacies receive

Employers are waking up — auditing contracts, carving out benefits, and backing unbundled models like Blue Shield’s $500M shift

Cost Plus, SmithRx, and others are attacking the model — rebuilding trust in a $450B market overdue for a reset

Why does my Amazon prescription cost $3 cash—but $10 with insurance?

“Why does insurance sometimes make my medication more expensive?”

A few healthcare-savvy friends asked me recently, and none of us could explain it clearly.

Behind every prescription is a choreographed system: drug manufacturers, wholesalers, PBMs, pharmacies, and payers—each optimizing for their own economics. Each player adds value and extracts it.

Prescription drugs now make up the third largest category of U.S. healthcare spend, nearly $450B annually or 9% of total (CMS 2023).

What follows is a map of how a pill gets to your hand, and who profits along the way. First, we’ll unpack who pays whom, and for what. Then, we’ll break down the models reshaping that structure. Finally, we’ll explore why the shift is happening now and where it might lead.

The Pharmacy Value Chain: Who Touches Your Script?

Let’s start with the basics. There are five key players we need to name (six, if you count the patient). First, the supply chain—entities that physically handle the drug:

Manufacturers: Develop the drug and set a list price (e.g., Pfizer)

Wholesalers: Buy drugs in bulk from the manufacturer, distribute to pharmacies (e.g., McKesson)

Pharmacies: Dispense drugs to patients via retail locations or by mail (e.g., CVS)

Then, we have the benefits infrastructure—layers that govern access and pricing:

Pharmacy Benefit Managers: Negotiate rates with manufacturers, manage formularies, and process claims (e.g., OptumRx)

Health Plans / Insurers: Pay claims, contract with PBMs, set member cost-sharing (e.g., UnitedHealthCare)

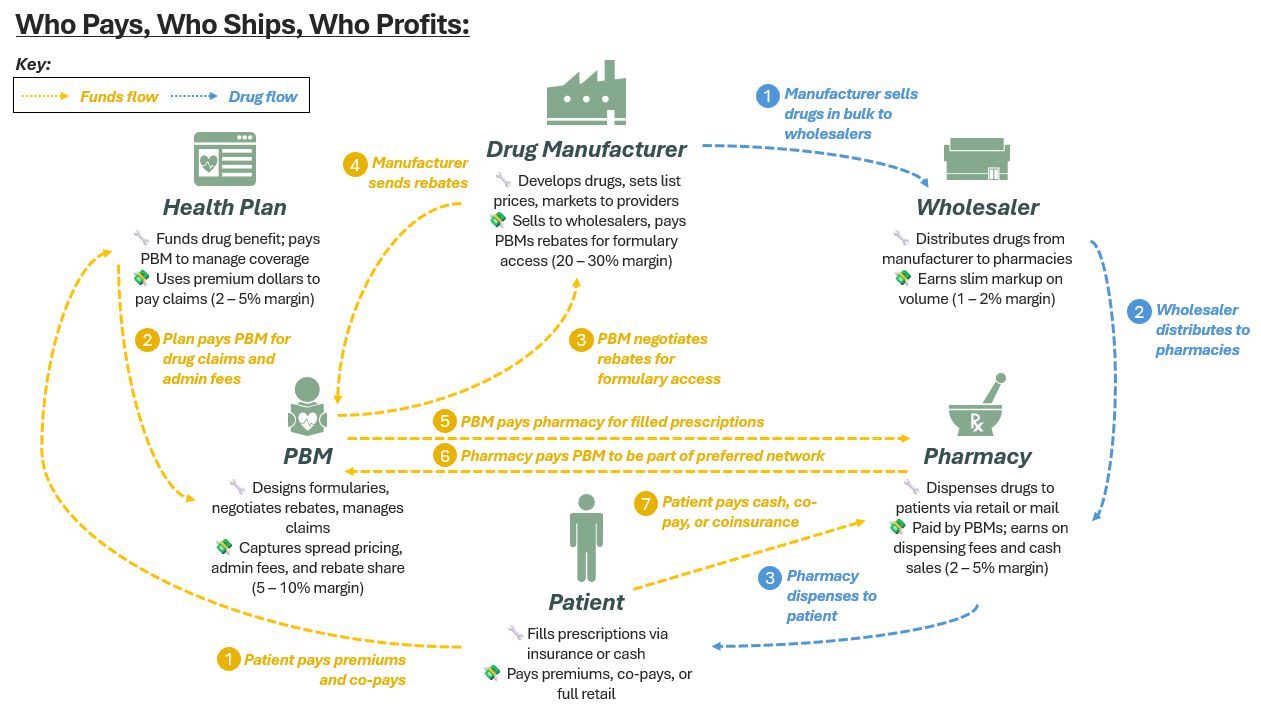

While the drug itself flows one way (manufacturer → wholesaler → pharmacy → patient), the money moves in multiple directions.

Payments, rebates, and fees snake upstream through the system, obscured from view. The price the patient pays rarely reflects the true production cost, or even what the pharmacy was reimbursed.

The diagram below traces these flows, mapping who does what, who pays whom, and where value is extracted along the way.

Even on paper, the system looks disorderly. Several steps in the funds flow introduce serious misalignment:

Skittle 4: Manufacturers pay rebates to PBMs for formulary placement, but patients rarely benefit. For example, Ozempic may have a $935 list price and a $400 rebate. Yet, the patient’s 20% co-insurance is still based on the full list price ($187). PBMs often retain 5–10% of those rebates, without disclosing the true share to the plan.

(The % of rebates retained is still up for debate. In its 2023 SEC filing, Express Scripts revealed retainment of 5%. Historical analyses from the Drug Channels Institute suggest rebate retention reached as high as 27% over the past decade).

Skittle 5: PBMs often reimburse pharmacies less than what they charge the health plan, pocketing the spread. Third-party audits have documented spreads of $20 per script, though in conversations with PBM challengers, we’ve heard estimates as high as $60 per fill (Source).

Skittle 2: The health plan (i.e., the employer in a self-funded setup) receives only partial insight into what they’re paying. Even when rebates are shared, the retained portion (the “rebate spread”) and network fees, including per claim deductions paid by pharmacies (Skittle 6) to remain in preferred networks, are invisible to the plan sponsor.

(Network fees can take the form of administrative or performance-based claw-backs, and while amounts vary, CMS and others have flagged them as a key source of hidden PBM margin.

These aren’t edge cases, they’re systemic. And at the center of them all? The PBM.

PBMs: The System Behind the System

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) are among the most powerful, and least understood, middlemen in the drug supply chain. Sitting between manufacturers and payers, they shape not just what medications are covered, but how they’re priced, accessed, and reimbursed.

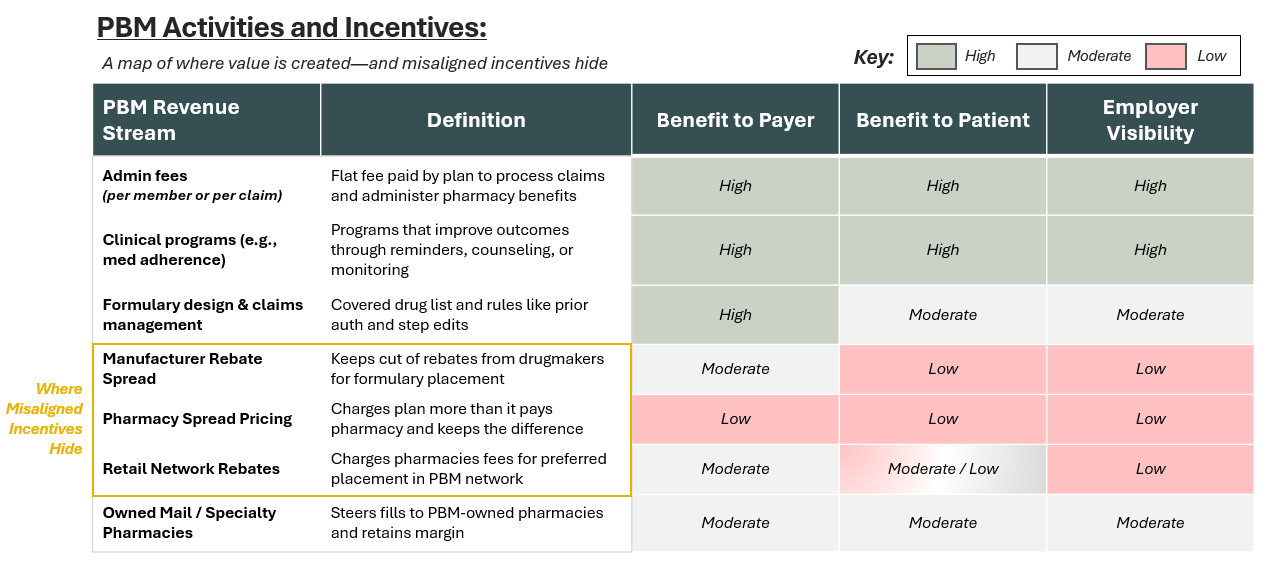

Their job is twofold: 1) manage the drug benefit and 2) find margin within it.

PBMs provide real services. They design formularies, negotiate with manufacturers, process claims, and contract with pharmacies. Many also operate their own mail-order and specialty pharmacies.

But alongside these functions, PBMs profit from structural opacity in ways that patients, employers, and even brokers rarely see.

Three friction points (as explored visually in the skittles we referenced before) highlight how incentives can quietly drift out of alignment:

Spread pricing means PBMs keep dollars that could benefit the plan (or the patient): Plans are billed more than PBMs pay pharmacies.

Rebate optimization means PBMs don’t choose the lowest-cost drug: PBMs are incentivized to prioritize higher-cost, branded drugs with larger rebates (paid by manufacturers) over cheaper alternatives.

Pharmacy networks are governed by their willingness to pay PBMs, not by patient access or convenience: Pharmacies pay PBMs for preferred status, shaping networks around financial relationships, not access or value.

These aren’t side effects. They’re embedded features (not bugs) of the model. Critics say PBMs are incentivized to drive up costs and restrict access. Defenders argue they prevent fraud and negotiate better net pricing.

The real problem? Employers don’t know what they’re buying—or whether they’re getting a good deal. Some have started using audit tools (e.g., Artemis, Truveris, Rx Savings), but those are Band-Aids, not a fix for structural opacity.

(It doesn’t help that many brokers guiding employers also receive overrides or commissions from the PBMs they recommend.)

PBMs aren’t going away, but their margins (and mystique) are finally under fire.

That tension is exactly what new pharmacy models are targeting: less complexity, more control.

What’s Emerging: New Pharmacy Models

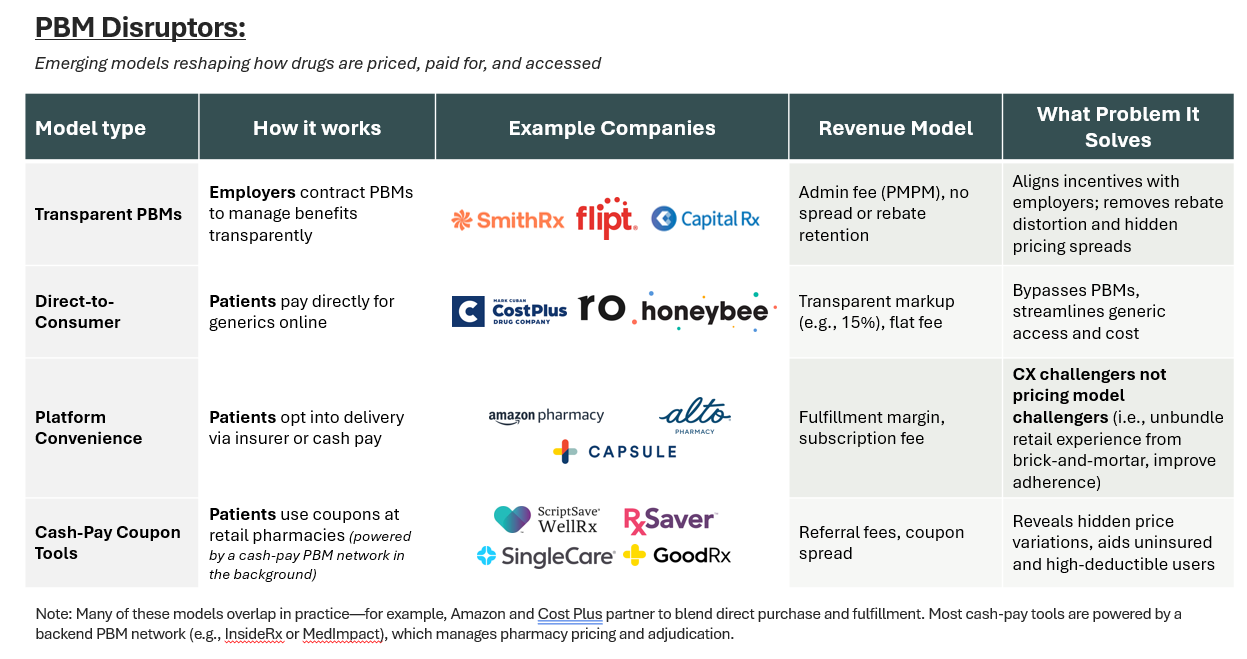

Disruptors don’t follow one playbook. They’re reimaginging different parts of the pharmacy stack, solving different problems with different models. Here's a quick taxonomy:

Disruptors are segmenting along strategic theses:

Transparent PBMs (e.g., SmithRx) align with employers by eliminating spread pricing and charging flat admin fees.

Direct-to-consumer platforms (e.g., Cost Plus Drugs) bypass insurance entirely, using transparent pricing as a trust wedge.

Coupon tools (e.g., GoodRx, SingleCare) sit atop legacy PBMs, monetizing price discovery via referral fees and coupon spread.

Horizontal plays are emerging—analytics, affordability tools, and fulfillment layers that integrate across benefit stacks.

The common bet? That clarity, not leverage, defines the next generation of pharmacy winners.

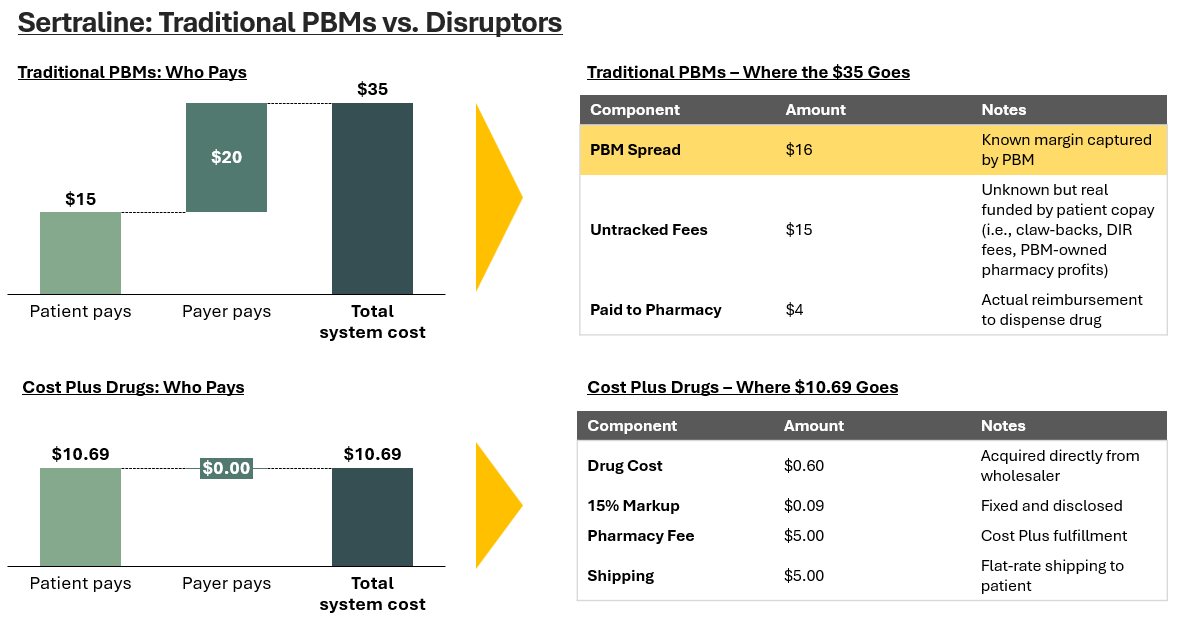

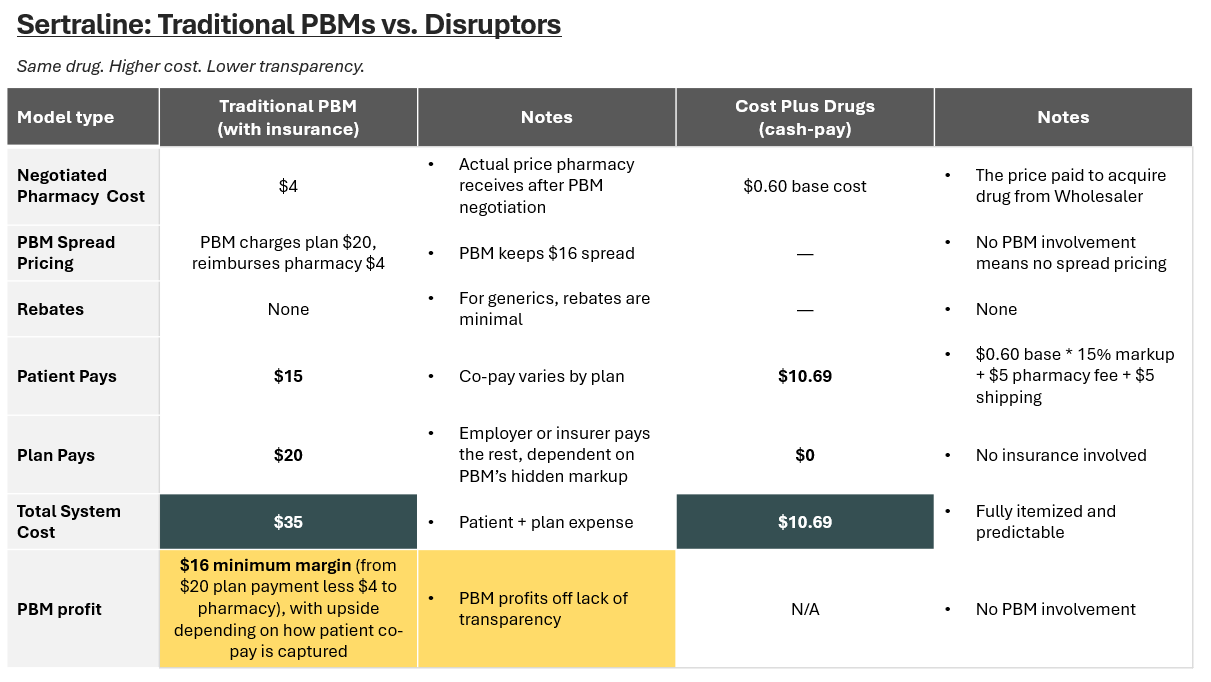

For an illustrative example, take Sertraline, the generic version of Zoloft and one of the most prescribed antidepressants in America (40M scripts in 2022).

A 30-day supply of Sertraline often costs more with insurance ($15 - 20) than it does with cash ($10.69 via Cost Plus Drugs) (source).

Here’s how the two models compare:

The key difference? Cost Plus cuts out the PBM entirely by buying directly from the wholesaler and fulfilling as the pharmacy.

While most associate spread pricing with high-cost specialty drugs, it’s most extreme in generics. Acquisition costs are so low that PBMs can charge $10 for a $2 drug and pocket the difference.

Estimates suggest spreads reach 30% on generics and 5–10% on specialty drugs. A $20 distortion on a single fill might seem minor, until you remember there are over 40M sertraline scripts written each year.

If this kind of markup exists on one of the cheapest generics, imagine what’s happening with injectables, GLP-1s, or oncology meds…

Why Now? Five Forces Colliding

The pharmacy value chain isn’t just inefficient, it’s unsustainable. Five forces are converging to accelerate change:

1. Specialty Drug Costs Are Soaring

U.S. prescription drug spend topped $800B in 2024, a increase of 10% year-over-year. Nearly half of that comes from specialty drugs (source). GLP-1s alone are projected to reach a $100B+ global market by 2030 (source). Employers want alternatives with more control.

2. Employers Are Fed Up

Self-funded plans face 6 – 9% annual increases in pharmacy spend—over 20% for plans with significant GLP-1 utilization (source). Broker incentives only deepen that misalignment.

3. PBM Margins Are High and Under Fire

The Big Three PBMs—CVS Caremark, OptumRx, and Express Scripts— control 80% of the market and earned $1.4 billion through spread pricing—charging health plans more than they reimbursed pharmacies for the same drugs (FTC). A 2024 lawsuit now alleges anticompetitive practices.

4. Disruption Has a Blueprint

As of 2025, Blue Shield of California dropped CVS Caremark and rebuilt its pharmacy stack through braided offerings from Cost Plus, Amazon, and Abarca. Despite being a major plan with scale and bargaining power, it expects to save $500M annually. If they were overpaying, smaller buyers likely are too.

5. Patients Are Asking Better Questions

Platforms like GoodRx and Cost Plus have changed expectations. Many now realize insurance isn’t always the cheapest (even if they don’t understand why).

That said, the answer isn’t one winner. It’s a set of clearer models, each solving a different piece of the puzzle. Some will scale. Others will specialize. But all are competing on the same thing: trust.

The Road Ahead: Not One Winner, But Many

No single model will fix the pharmacy system.

Cash-pay platforms work for consumers but fragment care

Transparent PBMs help employers but rely on pharma rebates

Vertically integrated giants have scale but wrestle with cost vs. access

What’s clear is this: the pharmacy stack is unbundling. And companies that clarify rather than obfuscate will earn trust and market share.

If the last decade was about building scale and leverage, the next one might be about something else entirely: clarity.

💭 If this sparked something—hit the 💜 or leave a comment. I’d love to know what’s worth unpacking next. Or forward it to someone building in the space.

Liked this one? You might also like The Ambient Scribe Stack — a breakdown on how companies like Abridge, Ambience, and DAX are going beyond the note to rewire clinical workflows.

In-Network is where I write about the business of care: models, margins, and the infrastructure behind how we deliver it.

→ Subscribe for sharp, honest analysis on what’s actually changing in healthcare.